Money, banking & insurance

Anti-cash rhetoric

The question whether physical money will disappear keeps ebbing and flowing, depending on the economy and our need for physical security to handle unforeseen emergencies. It does seem fairly inevitable that coins will disappear over the coming decades, but the abolition of paper currency could take far longer.

People who are old enough to have witnessed economic collapse and financial panic tend to like cash as a hedge against uncertainty. If interest rates are near zero, then the appeal of keeping money in a bank or savings account starts to evaporate. This is perhaps why recent demand for 20 and 50 pound notes in the UK has risen.

On the other hand, businesses, and especially governments, loathe cash. It’s liable to be stolen, costs money to handle and the existence of cash limits government ability to control the money supply – and therefore their citizens.

Some people claim that around 75 per cent of cash is used for untraceable illegal transactions so tax authorities would love to get rid of the loathsome encumbrance too. If cash disappears, governments can watch individuals more closely and there’s no limit to what they can do with negative interest rates.

In a recent speech, the chief Economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haladane, essentially proposed the abolition of paper currency as a solution to the problem of monetary control.

At the moment money is cheap. We’ve seen discussed capital controls around the edge of Europe and negative interest rates, where savers have to pay institutions to hold their money. At the same time, the European Central Bank is doing what is effectively the opposite: paying people to borrow from them.

It’s all a bit of a mess and adds to the potential volatility and uncertainty across much of the world.

Once most money becomes digital, then we all become entirely dependent upon the whim of government and at the mercy of bank failures, cyber attacks and systematic failures within the entire financial system. The end of cash is also the end of anonymity.

So here at What’s Next, our advice is to cash out now and stick a little something under the bed in case things really start to wobble.

Ref: Financial Times (UK), 5 December 2015, ‘Cash in the attic? Don’t tell the Bank of England’ by M. Somerset Webb. www.ft.com

See also, Daily Telegraph, 22 February 2015, ‘The chilling potential of sub-zero rates’, by P. Spence. www.telegraph.co.uk

Search words: Money, cash, digital currency, banks

Trend tags: Digitalisation

Rise of the algorithmic advisor

Look out, the robots are coming. Due to recent mis-selling scandals, pensioners are turning to robots for low-cost financial advice.

LV=, a savings, investment and insurance provider, has launched an automated advisor that can tailor suggestions to peoples’ specific risk profiles and financial goals. The service, known as Cora, offers ‘fully regulated’ retirement advice and mimics what a human professional advisor would do in similar circumstances, but in less time and, one assumes, at much lower cost.

New rules allowing the over-55s to take more control over their own pensions, along with government desire to reduce burearacracy and costs, will no doubt boost such services. But the idea that machines will automatically be more impartial than people is misleading.

Algorithms are programmed by people and these people might make human mistakes.

Ref: Financial Times (UK), 7 November 2015, ‘Rise of the retirement robots’ by J. Cumbo and (same issue) ’Rise of the robo advisor as pensioners are steered towards cheaper counsel’ by J. Cumbo. www.ft.com

Search words: Money, advice, robots, automation

Trend tags: Automation

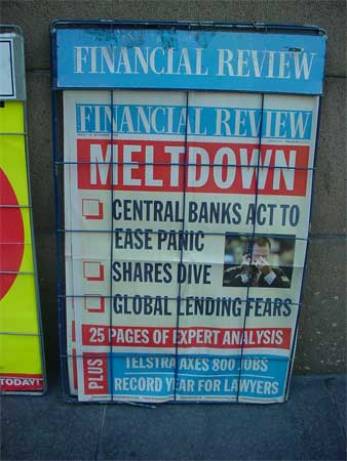

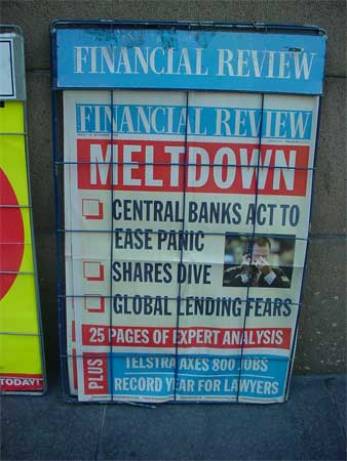

Big investment questions for 2016

What is the outlook for 2016? We’d say volatile at best and scary at worst, but we’re not financial experts. So what are the real experts saying? A selection of global fund managers surveyed by the Financial Times highlights a few common questions.

The first is what will happen with US interest rates? The second is what will happen to China and the third concerns the outlook for Europe.

The danger with US interest rates is that any small rise could be interpreted as the start of a series of rises and this could spread panic, especially for individuals already stretched with loan repayments.

In China, the rest of the world was surprised last year when the government allowed its currency to depreciate. China desperately needs to rebalance its economic model away from exports towards internal consumption. But there are various ways in which this could tank, with a rapid slowdown quickly turning into a meltdown and an epidemic of capital flight.

Where to start with Europe? Overall, the best advice comes from David Harding of Winton Capital Management, who states that the only certainty is the role of the unexpected. It wasn’t too long ago that the world worried about $US200 oil. Now we worry about oil going below $US30. As Harding says: “It’s amazing how surprised people are by surprise.” Quite.

Ref: Financial Times (UK), 5-6 December 2015, ‘Fund managers focus on three big themes’, by D. McCrum, R. Wigglesworth, D. Oakley. www.ft.com

Search words: Risk, economy

Trend tags: Volatility, connectivity

Is the Eurozone doomed?

According to a former governor of the Bank of England, the Eurozone is doomed to fail and will stagger from one economic and political crisis to another unless it is broken up. The problem, in essence, is twofold.

First, a creeping transfer of sovereignty by an unaccountable economic centre is clashing with local concerns and local resistance. The EU has created the largest monetary experiment in history, but the experiment hinges upon a forced marriage between supra-national political idealism and local economic arithmetic.

The wealthy and economically competitive European North and West (the creditor nations generally speaking) are clashing with a relatively poor and uncompetitive European South and East (the debtor nations). This explosive dynamic is intensified by a single interest rate leading to further divergences, especially as all the debt is denominated in a currency that is likely to rise.

Second, there’s the problem that the centre won't see - the illusion that creditors will always be repaid - so the solution to any crisis is to lend the debtors more money or extend the repayment terms for the debt.

Is there a solution? One answer is to shrink the number of member nations by throwing the weaker countries out. This would cause extreme pain in the short term, but it could be argued that it’s better than a long drawn out death. The alternative would be a weakening or loosening of social and economic ties.

However, both options are the last things that any bureaucracy hell-bent on expanding its power base will actually do. Personally, our money is on populist politicians in Germany deciding they will no longer support their weaker brethren, thereby forcing a collapse. Ridiculous? Give it time…

Ref: Daily Telegraph (UK) 29 February 2016, ‘Eurozone ‘is doomed to stumble from crisis to crisis’, by S. Ping Chan

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

Search words: Europe, EU, risk, uncertainty

Trend tags: -

The establishment v the anti-establishment

One of the biggest problems facing policy makers and economists now is the growing sense of inequality around the world.

For example, in the US CEOs typically earned 20 times the pay of their average worker in the 1950s but today the ratio is 200. But the biggest problem of all may be the feeling of vulnerability and lack of control that accompanies it.

Why is this happening? One reason might be globalisation and another digitalisation. But as JK Galbraith once commented, the erosion of trade unions and civic organisations removed a “countervailing force” to big business and unrestrained free-market capitalism.

How this trend will end is unclear, although one possible consequence is emergence of populist politicians or ‘non-political’ politicians, such as Donald Trump. These people represent a significant shift away from left versus right to establishment versus anti-establishment.

The bugbear is not just money. The focus currently seems to be on what some people have and what others don’t, but perhaps this should shift to what people actually need. This links with the idea of a basic universal income, as well as broadening the debate to include education and health as well as money.

Ref: Financial Times (UK) 10/11 October 2015, ‘The few and the many’, by J. Baggini. www.ft.com

Book links: On inequality by Harry Frankfurt, The Health Gap by Michael Marmont, Saving capitalism by Robert Reich and The Economics of Inequality by Thomas Piketty.

Search words: Voting, populism, CEOs, pay

Trend tags: Inequality